Not all fetures sent in to Adventure can go in teh magazine -but they can go online for you to enjoy – here is Russell Tregonning story

Bloody hell! Something’s wrong. Brakes aren’t holding. I’m in trouble.

A viral chest infection stops me biking so I’m the designated van driver following my biking mates to pick up stragglers. The hired vehicle is dragging a heavy bike rack down a steep winding descent to the river crossing below.

Suddenly, I’m frightened, my chest is tight and I’m breathing fast. I fear I’ll have to run into the bank to stop. I yank hard on the hand brake, grinding to a halt with a graunch, stones flying off the unsealed surface as I swing onto the side of the road. Whew – that was close!

I’m part of our self-styled ‘Men of Steel’, a group of cyclists, we have biked for a week each year somewhere in rural New Zealand. I’m on the Dansey’s Pass road, one of the most isolated high country routes in New Zealand. This is the 30th anniversary of the first trip we made – along this same route in 1995 – five days biking from Tekapo to the Taieri via the Waitaki valley and Maniatoto. The first trip we rode on conventional machines – muscle-driven bikes; to save weight, one pair of back-up undies and cut-down tooth brush; all non-riding gear carted on our backs or in saddle bags; no accompanying vehicle. This time we ride modern electrically-assisted bikes and, for some distance, we ride in luxury in a back-up van with no luggage restrictions. The years have turned steel to cotton wool.

Hand poised over the hand brake, and heart in mouth, I venture slowly downwards. Plumb in the middle of the one-way bridge the van stalls. I can’t restart it. The engine is dead. There is a car ahead wanting to cross, headlights flashing, warning me to get clear. A group of cyclists – not ours – is resting by the bridge and they, like me can hear a whirring noise coming from the van. One of them yells out,

‘Turn off the fuck’n air con’.

‘It isn’t on’, I yell back. But I feel incompetent and humiliated in front of them as they push van, me and trailer off the bridge, clearing the way for the car ahead. When they take off up the road, I shout at their backs,

‘Many thanks, guys. If you catch up on my bike-mates can you please tell that I’m stuck’.

I hold out little hope. There is no cell phone reception, so I hail a small motor home: mana from heaven – two young Belgium women – angels of mercy.

‘Shove your bike in the back and we’ll take you up to your friends’.

And so they do; and then return for our luggage, delivering it to our accommodation in Ranfurly. We leave the stricken van for the AA to pick up. Then plan B as one of our group arranges for his wife to deliver his 4WD from Wanaka so we can continue our itinerary.

On the final day, the weather breaks – too dangerous to bike over the Dunstan trail, the old goldminers’ route into Central Otago over the Rock and Pillar mountain range. We know the history: in the 1860s, miners died from exposure up there in the bleak, isolated country when trapped in snow storms – no trees for cover, nor firewood for warmth. We’re not going to risk it.

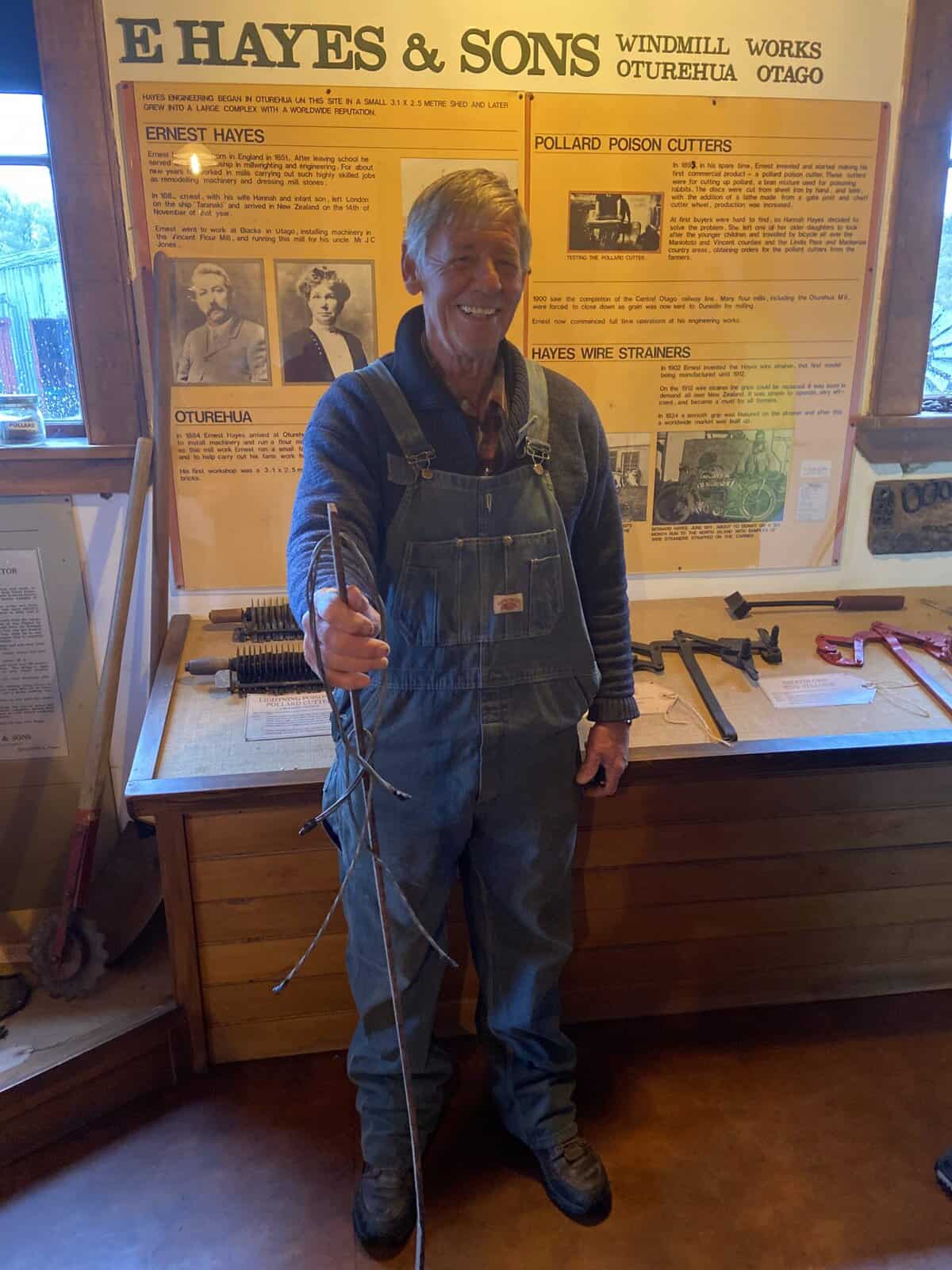

Instead, generous Oturehua local farmer, Ken Gillespie, guides us around the Hayes Engineering Works. Ken tells us of the pioneer Ernest Hayes, an English trained millwright and engineer who in the 1880s opened his factory with machines to make numerous farming implements. His invention of the fencing wire strainer, still widely used today, surely makes him a founding father of our much-celebrated number 8 wire technology. His wife Hannah, mother of nine, biked around Otago as salesperson.

When Ken turns on the electricity – now from the national grid rather than from Hayes old wind and water generators on site – we see and hear a multitude of clanking wheels, belts and drive shafts powering machines to bend, punch and bore holes through fencing standards and other metal appliances. Although the machinery has been upgraded to it’s new electricity source and other modern modifications made, many parts look about 140 years old, and still working like new – this ancient machinery running like clockwork in front of us. Our vehicle, a modern machine lies still, lifeless, abandoned in the mountains.

Have we made progress?

( This article is based on a similar, published in the Oturehua Newsletter, April 2025)