Butt Hurt – What happens when a first-ascent mission leaves you with a broken tailbone

From Adventure Issue 233 ????

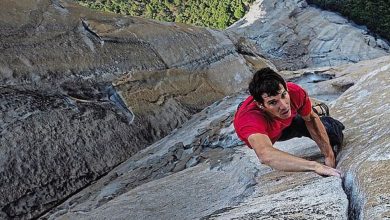

A guttural yelp escaped my lips, the kind that betrays the unexpected and the terrifying. My foot had slipped off the rock-face, and suddenly I was falling. Having placed no protective gear so far, the only possible outcome was a ground-fall.

I slammed into the hard edge of a natural water trench at the base of a cliff in the remote, wild, intimidating Darran Mountains of northern Fiordland. I had only been a few metres off the ground, but the pain was immediate. It took me several moments to untangle from the crumpled heap I’d collapsed into.

It was around then that I realised that I’d left my first aid kit in my backpack at our bivvy site at the top of the valley. We were a long way from there. We had abseiled into the valley, and then danger-walked—including lowering ourselves from handfuls of snowgrass—down challenging terrain to arrive at the base of this virgin 300m-high wall of rock. In other words, it had been quite involved to get to where we were, and we’d never been there before, meaning we had no idea about the best way back up.

The plan had been to climb the wall, including a 150m chimney between the wall and a gargantuan mega-block sitting in front of it, followed by a 150m headwall, before heading back to the bivvy that evening. My fall forced a change of plans.

It was just after 1pm, and my immediate response was to insist that my climbing partners, Jimmy and Ben, attempt the chimney, given we were already here. How long could it take, anyway? It looked straight-forward, and my pain levels weren’t astronomical.

As with many first ascents, it predictably took much longer than anticipated. They returned in the evening light, just after 7pm, having chimneyed for hours on an all-time adventure. I was still too sore to climb, but I also happened to be on a lovely ledge of tussock, which was near a natural trench of running water. In staying the night, I’d be a bit cold and uncomfortable, but my life wouldn’t be in any danger. Jimmy would later name this place Camp Derek, given how it came to be.

Jimmy left me his down jacket and I settled in for the night, watching their head-torches as they moved up a wall they hoped would be the quickest way out. Again, and not unpredictably, they got much more than they bargained for. It took four pitches of sparsely-protected climbing, meaning any falls would be long and potentially dangerous, before they topped out—thankfully fall-free.

It was 3am when they reached the top of the valley. The following morning, Jimmy decided to take all of our gear from the bivvy spot to Camp Derek in case, due to my injuries, it was best to head back to civilisation from there. It was about 24 hours after my fall when they managed to return with my first aid kit, and some food. By then, my morning shivers had dissipated; Camp Derek was basking in afternoon sunshine.

Tramadol and ibuprofen brought relief. It wasn’t until several weeks later that I realised I’d probably broken my tailbone. My self-diagnosis was based on the acute pain I felt when sitting or lying in certain positions. And there was one particularly telling symptom: for weeks, it was really painful to shit.

I’d met Jimmy and Ben the previous summer in Homer Hut, in Fiordland, and quickly learned that Jimmy was basically Mr Darrans; he always knew exactly where we were, which peaks we were looking at, and the best way to proceed from wherever we happened to be. Ben was also an ideal Darrans companion for his easy-going nature, rope expertise, and his penchant for calorie-rich butter, and his willingness to carry it to remote places.

Having spied some neck-craning, virgin rock a few weeks earlier on his way out from Tutoko Valley, Jimmy had enlisted us for a first-ascent mission. I’d done some first ascents before but never in the steep, glacier-carved rock walls of the Darrans, where the scenery and the sense of adventure are the finest in the country.

We had trudged in with several days of food and a week-long weather window, so I saw no point in heading down because of my tailbone woes. At worst, I could sit and relax on tramadol vibes at Camp Derek while Jimmy and Ben explored the cliffs.

By the following morning, however, I felt sufficiently drugged up to put my butt to the test. The upper face of the detached mega-block appeared to be blessed with twin cracks, while the lower face offered a few potential paths to access them. With more than a touch of nerves and an abundance of tramadol, I chose the line of least resistance.

I went into a slight panic when, about eight metres up, my attempt to widen my stance in the middle of a stem corner was met with a sharp butt-pain. I had to improvise, climbing the face before traversing onto slabbier terrain.

When we reached the upper face, I started up the left crack because the right one, uninvitingly, was full of loose blocks of rock. But higher up, I became increasingly tangled in mental knots and physical shakes, and I eventually slumped onto the rope. I offered the lead to Ben, who lowered me and took over, climbing above my high point where the crack became increasingly flora-filled.

It’s not easy to trust handfuls of bushes with all of your weight on vertical terrain. With his forearms ablaze with lactic acid, Ben yelled down a warning to me that he was going to fall. I braced myself, but he’s decently heavier than me, and catching him catapulted me upwards and across the cliff, my head, shoulders and back rag-dolling against it as I spun uncontrollably.

When I settled, I realised my right shoulder was bleeding. I had been slung 20m across the wall, which had eaten a 4cm-long chunk of flesh from it. Luckily, as if I was prepared for this exact scenario, I had a pocket full of tramadol.

Ben eventually pulled back onto the wall, traversing to the right crack to avoid the tenuous bush-pulling. The real motivation for the day’s mission became apparent once we were on top of the mega-block; Ben had left his camera there after topping out the chimney two days earlier, and had wanted to retrieve it.

The 150m headwall above us looked thin, hard and, in the blazing, afternoon sun, unappealing. We descended. Even though I’d added a bleeding shoulder to my woes, it felt invigorating to have climbed something new.

We experienced the same high the following day, though inadvertently. Ben and I headed for what we thought was the South Ridge of Milne (grade 18). But Milne is incorrectly labelled on the NZ Topo Maps app, which we were using to navigate, so we ended up climbing the south ridge of point 2135–an easy and worthwhile scramble with two summits, and maybe a few moves of grade 14.

We faced one final uncertainty on our last morning: a first descent from Camp Derek down to the Tutoko River. It started with abseils down slabs, which converged on water-worn channels and steep waterfalls. Avoiding these, we traversed and scrambled down verdant slopes to the north. When they, too, became too steep, we abseiled off shrubs and, at one point, even a flax bush.

Eventually we had no option but to join the flow of water, where the down-climbing took on more of a canyoning aspect. As if to reward us, a pool of the clearest turquoise greeted us near the bottom, where a quick dip in the afternoon sunshine was obligatory. From there, with the biggest dangers finally behind us, we had a leisurely stroll alongside the Tutoko River to the Milford Road.

So, what did I learn? I learned that it’s easy to make mistakes, despite years of experience and, frankly, knowing better. I should have had my first aid kit close to hand. I should have anchored myself to the wall—which I did, but didn’t do well—to avoid being catapulted across it when catching Ben’s fall. I should have planned for the unexpected.

The question of whether it’s worth it always hangs over any adventure to the remote parts of the Darrans. The approaches are long and challenging, the weather often volatile, and the climbing challenging not just in difficulty, but also in how safe it may or may not be. Such adventures are not for everyone.

Add in the uncertainty of first-ascent hunting, and the question of whether it’s worth it only amplifies. But the potential rewards are also amplified.

And if you don’t go, you’ll never know.

—

https://www.facebook.com/dirtbagdispatches

https://www.instagram.com/dirtbagdispatches