“The world has sort of already ended…”

An interview with mountain biker and academic Dr James Cherrington

“The world has sort of already ended… not this Hollywood apocalyptic notion of it exploding and meteors crashing into the earth, but practically and conceptually the world as we knew it has disappeared.”

Jim is a senior lecturer in the Academy of Sport and Physical Activity at Sheffield Hallam University and passionate mountain biker. I was interested to talk to him about a number of ideas that show up in his work, such as the notion that pure nature doesn’t exist anymore and that we’re already experiencing the end of the world (see also the work of Alex Steffen), though Jim explores this in an altogether more hopeful way than it sounds. We also talk about the power of skateboarding to give communities agency in Jamaica and the role action sports can play in giving all of us a break from reality.

I hope you enjoy our chat.

Hey Jim, how are the trails? Have you been out riding a lot lately?

I usually ride two-three times a week, and honestly, the conditions have been awful recently haha. We’ve had a lot of rain these past few months so everything’s all chewed up and mucky, but fortunately the last couple of rides have been a little drier.

Last year, you co-authored a book called Sport & Physical Activity in Catastrophic Environments. How did that come about?

It was a bit of a weird one as I’m used to studying stuff that’s a bit more cheerful and happy, but I spent the last two years thinking about the end of the world.

Tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, wildfires, and droughts are increasingly commonplace, along with less obvious forms of social catastrophe that often go unnoticed in the media, such as poverty, isolation, and mental health problems are skyrocketing…

The book was an attempt to redefine how we think about these social, natural, political, and moral problems, and to bring some hope into these discussions by looking at the role that physical activity can play in helping people deal with catastrophes when they happen but also whether they can help people preempt these catastrophes.

We make a bold claim in the intro that the world has sort of already ended and what we mean is not this Hollywood apocalyptic notion of it exploding and meteors crashing into the earth, but practically and conceptually the world as we knew it has disappeared. And accepting that is important because there is then optimism in that acceptance, in acknowledging the end of the world, we open ourselves up to new worlds.

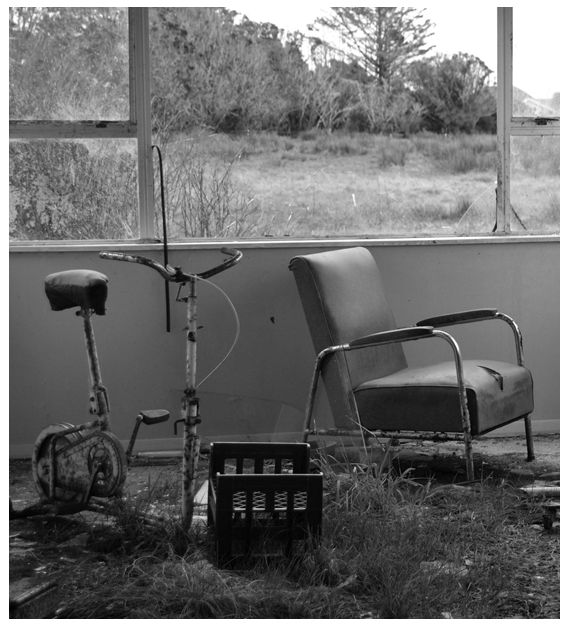

Ph: Kevin Bingham

In the book, there’s a chapter on DIY skate parks in Jamaica…

Yes, I worked on that with Tom Critchley. He did some work in Kingston centred on The Gully DIY spot. It’s an institution that is trying to bring together people who live in poverty, and he argues that skateboarding can help us reimagine a world after capitalism.

Capitalism in Jamaica, as well as forms of imperialism, have seen the west determine what happens over there and contribute to the poverty that Jamaicans suffer. The Gully is a collaborative project which empowers local people to make decisions over how funding is used, how the space is used, they work together to formulate a plan of action for the skate park and engage people who are living in poverty. And overall, it illustrates how we can move beyond a world that is just about making profit and commodifying sports like skateboarding.

There is a lot of good writing from academics where they deconstruct the model of the west in helping people in places like Jamaica and countries in Africa, where these projects are defined in faraway places without any understanding of what the locals want. You often find it isn’t money that people want, they want to be better educated and empowered and to have a voice. And in the case of physical activity, to engage in something like skateboarding with all the creativity and freedom it brings without impediment or having to answer to anybody. Tom argues the Gully skatepark allows them to do that.

Thanks for reading Climate & Board Sports! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Can a skatepark and skateboarding generally be separated from the capitalist system?

An analogy I always use when I’m trying to explain this is, if you have a band like Rage Against the Machine, they’re anti-capitalist in ethos but signed by Sony, arguably one of the biggest capitalistic conglomerates in electronics on the planet. But the band’s counter argument is a valid one, they would say you can’t completely revolutionise the system overnight, you have to beat it from within, and that would be Tom’s argument in relation to skateboarding. Skateboarding isn’t going to save the world right now, but these small contributions can help towards longitudinal change.

And they can also provide temporary relief for skateboarders in terms of escaping that system and providing hope, which is a really powerful thing.

How important are sports like snowboarding, surfing and skateboarding in giving people the ability to take a pause from their everyday concerns?

As a form of catharsis and general release from everything that is going on, including the climate crisis, action sports can be really effective. I talk about this in my chapter on mountain biking and as a mountain biker myself that’s one of the reasons I do it.

But I am a big advocate of that not being enough. If you’re going to make a claim for action sports disrupting what is normal and accepted, it has to go beyond that. That doesn’t necessarily mean we need people to be going out and protesting or holding up sandwich boards saying they’re against the climate crisis, but people do have to adopt some kind of critical sensibilities and a different way of looking at things like climate crisis through that activity.

I don’t think nature in its purest form exists anymore. Everywhere we go and everything we see, that is supposedly natural, has had some kind of human influence on it. Soils have been affected by the movement of people and animals, water has been affected by pollution, there’s acid rain, chemicals in the atmosphere that shouldn’t be there…

People need to accept that pure nature, if it ever existed, doesn’t exist in the way we used to think it did, and I would argue to think that way now is irresponsible. I obviously still think it’s really important to care for birds and rivers and trees and landscapes but if we think nature is out there and different from us then we treat it as such. And that’s when things like pollution are increased because we flush our toilet and our sewage goes out there and we can forget about it, the same thing with our bin waste going into landfill. We have to acknowledge that we have a direct impact on nature, and we are closely connected to it and mountain biking is a good facilitator of that attitude.

Could you expand on that a little more?

People will say mountain bikes don’t belong in the countryside as they’re not natural and they are a form of technology, but humans are co-determined by their technologies and always have been. From when we first started walking upright and using knives and forks and implements to break things and eat things, we became technological beings.

Clifton Evers, [who I interviewed last year], did some fantastic work on surfing in the north-east of England, and how the sewage and pollution there is really sad and tragic, and a catastrophe in its own right, but it’s also just the kind of thing that surfers there have to get used to now. But it completely changes the dynamic between sport and health, doesn’t it? We used to seek solace in these blue spaces as they were healthy and wild and untouched and pure and now, they’re none of those things so it raises questions over what is healthy and what isn’t.

You talk about therapeutic prescriptions in the book and imagine a world where we don’t just think about money or survival but how to be happy or feel hope…

Yes, it was a term coined by a philosopher called Bernard Stiegler, who said there are certain technologies that help us develop better connections with nature, such as spades, bikes, and buckets. Using the spade as an example, I did some research with mountain bike trail builders a few years ago and found they had a really sophisticated relationship with dirt, they loved its smell and feel and used words and language to describe it that helped facilitate bonds amongst them. I imagine it’s the same with the sea for surfers or snow for snowboarders.

In the book you raise the point that many of us who take part in action sports are quite privileged…

It’s an important point and we’ve got to be careful about lauding or celebrating these kinds of sports and activities as a kind of panacea or worldwide solution to loneliness. We have a chapter on how helpful walking groups were to people during Covid but I would imagine that the majority of people who were engaged in groups of that nature were very white or middle class and therefore would have an understanding of the outdoors that other groups of people wouldn’t.

On the one hand, Covid could have potentially been very revolutionary socially because it could have changed the way we do everything but on the other hand in the context of physical activity, those who were already active were very active and those that weren’t either did the same amount of sport or less, as they were the ones having to engage in zero-hour contract work.

What more can we do as surfers, snowboarders, mountain bikers…?

Engage in personal forms of change, reflect on your own practice, the things you do, how frequently you travel to uplift mountain bike parks in another country, or fly to those lovely surf destinations, and have conversations with friends about this kind of stuff. Even if it’s only in a jokey way, at least you’re having those conversations.

You can have those breathtaking moments in sport with your riding or surfing buddies, where you’re looking up into the sky and imagining what the universe is like. Well, have those conversations about how political, structural, and more institutionalised forms of change might look as well. Go out there and join your local skate/surf/mountain bike advocacy group and spread the word.

Tom Campbell, who works for MTB Scotland, told me about a storm they had last winter which wiped out loads of the local trails as lots of trees fell down and caused carnage. But they had an unprecedented amount of people who came out to help rebuild the trails, people who had never contributed to trail maintenance or trail digging before, suddenly came out of the woodwork. He said it was a shame it takes something like that to affect people but perhaps it’s one of the things that acknowledging the end of the world might help us to do.

To find out more about Sport & Physical Activity in Catastrophic Environments head here.

Other news:

I’m heading to Croyde this weekend for the inauguration ceremony of North Devon as a World Surfing Reserve. Read more about the events t planned for this weekend here & look out for interviews with Adam Hall and Yvette Curtis from the team in the newsletter over the next few weeks.

Big ups to Finisterre’s increasing efforts at product circularity, from offering repairs and re-waterproofing on jackets (which I need to get involved in), and selling second hand products, to offering discounts if you trade in old Finisterre clothing. Read about their Lived & Loved campaign here.

Huck Magazine have redesigned their website, and set out a new bold online mission. Read editor Emma Garland talk about it here.

If you’re based in Brighton, here’s another shout out for the Surfers Against Sewage Paddle Out on May 20th.

Please fwd this newsletter to anyone who you think might be interested & if you have any story tips on any of these themes pls get in touch.

Thanks for reading Climate & Board Sports! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

by Sam Haddad